The Stories Church Leaders Tell

- Jan 9

- 4 min read

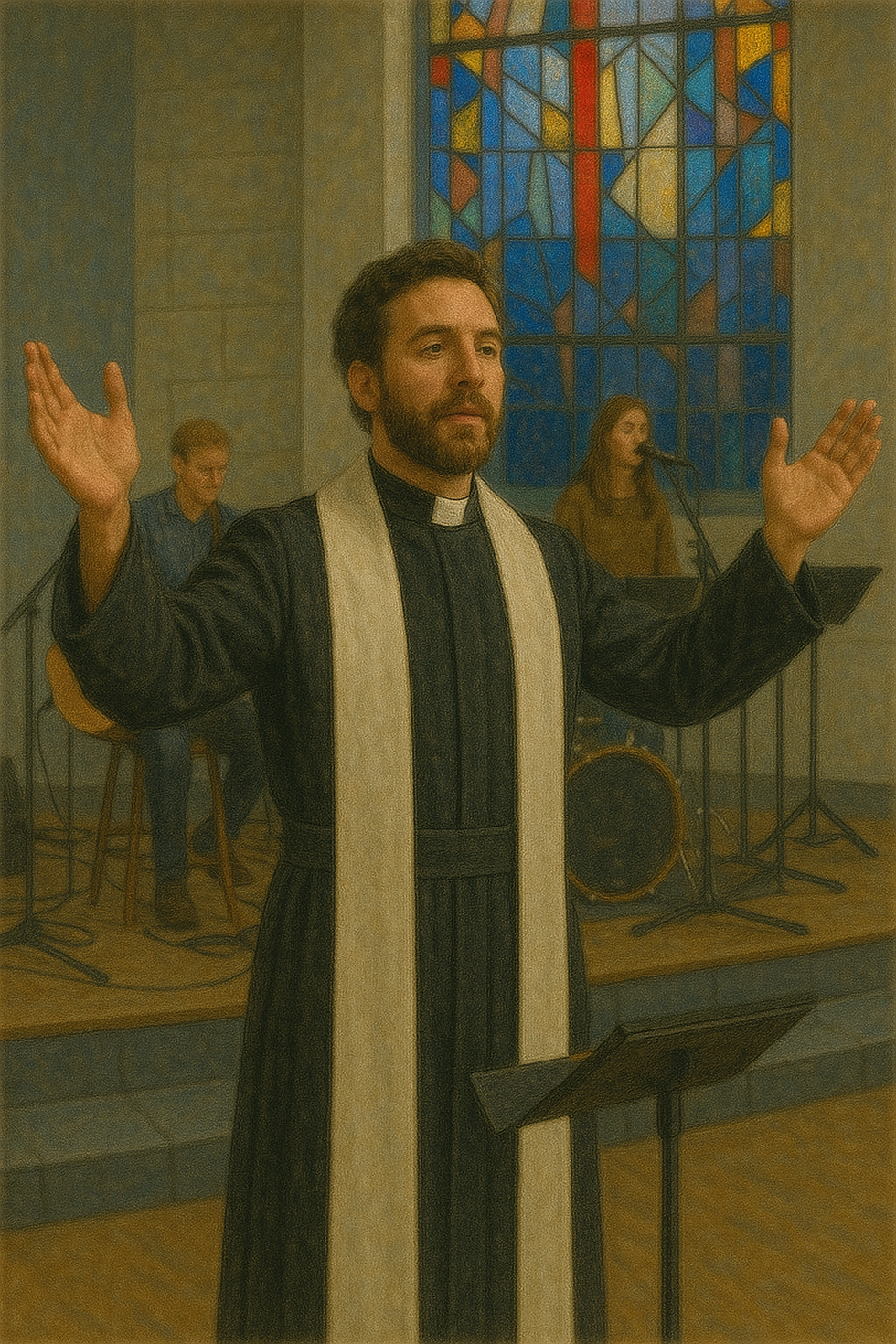

Church leaders are storytellers by vocation.

They retell the story of Jesus — not as a static account, but as a living narrative people are invited to inhabit. But they also tell other stories alongside this one: stories about the church itself — where it has come from, where it is going, and why it matters.

These stories circulate everywhere: sermons, leadership meetings, PCCs, reports, funding conversations, informal networks. Over time, they create a shared reality.

And that is where their power lies.

Stories do not simply describe what is happening. They decide what counts as happening. They shape which experiences are trusted, which voices are centred, and which interpretations are allowed to stand.

Stories of origin legitimise authority.

Stories of growth signal blessing.

Stories of success reassure those who need confidence.

Under pressure — institutional, financial, reputational — these stories can drift. Conflict is summarised. Loss is reframed. People who leave are explained rather than listened to. Complexity is smoothed out for the sake of coherence.

The story becomes compelling.

And less true.

Often this isn’t deliberate. Leaders feel responsible for stability. Ambiguity feels dangerous. Open-ended stories feel like failure. So the narrative tightens.

What remains is a dominant story — authorised and defended — while other accounts are quietly edged out. Those who question it are told it’s not the right forum. Those who persist are referred to process. Those who speak from pain are encouraged to let it go for the sake of unity.

This is where counter-testimony matters.

Scripture itself refuses a single, settled account. Alongside confident declarations of order and blessing sit cries of lament, protest, and accusation. These voices are not a threat to faith; they are part of its truth. The Bible preserves them rather than resolving them.

Churches often struggle to do the same.

Counter-testimony — stories told from the underside of power — interrupts momentum and complicates vision. Because it threatens the dominant narrative, it is often managed rather than received: reframed, psychologised, or met with silence.

Silence, too, is a story.

It teaches communities which truths are welcome and which are dangerous. It communicates that coherence matters more than reality.

Psychologists speak of schemas — the deep frameworks through which people interpret themselves, authority, and the world. Words spoken by leaders do not remain external. They settle into these frameworks and shape how people understand God and their place in the church. When counter-testimony is dismissed, the dominant story doesn’t just win — it reorganises meaning.

There is a point where this drift stops being accidental.

Narrative can be turned sideways — from meaning-making to containment. A person becomes a version of themselves that circulates without them. Motive replaces substance. Tone stands in for truth. Once established, such stories do not need defending; they simply persist.

In these moments, story functions as power.

This is especially dangerous when harm or abuse is involved.

History shows how carefully managed church stories — half-truths, omissions, and silences — have protected institutions while compounding the suffering of those already hurt. In such moments, counter-testimony is not disloyal. It is the only route to truth. External investigation is not a failure of faith, but an acknowledgement of the limits of internal narrative.

These dynamics also shape everyday church life.

We see them in (evangelical) testimony culture. Stories of decisive conversion and visible transformation are platformed. Stories of slow faith, doubt, mental illness, relapse, or unresolved grief are shortened or quietly sidelined.

We see them in how churches talk about joy and hope. We prefer stories that sound uplifted and resolved. Endurance without breakthrough rarely gets the microphone.

We see them in how churches talk about “serving the city” — celebrating activity and generosity while skirting harder realities: poverty, inequality, and the moral dangers of hoarded wealth.

These preferences are not neutral.

They teach people what kind of faith is acceptable.

I recognise this dynamic in myself.

As a leader, I know how easily stories drift — how origin stories become cleaner, how growth stories omit cost, how success stories absorb mistakes without naming them. I know how subtly the narrative can begin to orbit me unless I resist it.

That awareness has made me more careful.

The real question is not simply what story leaders tell, but which voices they allow to interrupt it — and which parts of themselves they are protecting when they do not.

The church does not need leaders who stop telling stories.

It needs leaders who tell less defended ones.

Stories that honour growth without denying loss.

Stories that allow joy without demanding performance.

Stories that refuse to become instruments of control.

Because the gospel story only stays alive when it remains open — open to interruption, protest, and truth spoken from the margins.

A church that cannot hear counter-testimony is not strong.

It is protected.

And faithful leadership is not about guarding the story —

but keeping it open enough for truth to speak.

⸻

Jon Swales

Comments